submitted by: Field Agent Nuwari Dharasulluman | Kenya (this information comes from www.africawithin.com), video by mosaic

Click here to view video

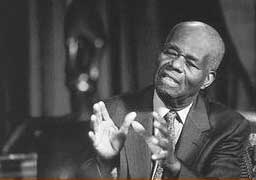

A Great and Mighty Walk by John Henrik Clarke

January 1, 1915 – July 16, 1998

On January 1, 1915 when I was born in Union Springs, Alabama, little black Alabama boys were not fully licensed to imagine themselves as conduits of social and political change. I remember when I was about three years old, I fell off something. I do not know what it was but I remember Uncle Henry putting some water on my head and I really do think that instead of the "fall" knocking something out of me, it knocked something into me. In fact, they called me "Bubba" and because I had the mind to do so, I decided to add the "e" to the family name "Clark" and changed the spelling of "Henry" to "Henrik," after the Scandinavian rebel playwright, Henrik Ibsen. I liked his spunk and the social issues he addressed in "A Doll's House." I understood that my family was rich in love but would probably never own the land my father, John, dreamed of owning. My mother, Willie Ella Mays Clarke, was a washerwoman for poor white folks in the area of Columbus, Georgia where the writer Carson McCullers once lived. My mother would go to the houses of these "folks" and pick up her laundry bundles and, pull them back home in a little red wagon, with me sitting on top. At the end of the week, she would collect her pay of about $3.00. My siblings are based in the varied ordering and descriptives that characterize traditional African diasporic families. They are Eddie Mary Clarke Hobbs, Walter Clarke, Hugo Oscar Clarke, Earline Clarke, Flossie Clarke (deceased), and Nathaniel Clarke (deceased). Together, in varied times and forms, we have known love. My loving sister Mary has always shared the pain and pleasure of my heartbeat in a unique and special way. We have sung our sad and warm songs together. But, we have all felt the warm rains of Spring, and felt the crispness of the fallen leaves in Fall together. As the eldest son of an Alabama sharecropper family, I was constantly troubled by a collage of North American southern behaviors and notions in reference to the inhumanity of my people. There were questions that I did not know how to ask but could, in my young, unsophisticated way, articulate a series of answers. My daddy wanted me to be a farmer; feel the smoothness of Alabama clay and become one of the first blacks in my town to own land. But, I was worried about my history being caked with that southern clay and I subscribed to a different kind of teaching and learning in my bones and in spirit.

I am a Nationalist, and a Pan-Africanist, first and foremost. I was well grounded in history before ever taking a history course. I did not spend much formal time in school—I had to work. I caddied for Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley long before they became Generals or President, for that matter. Just between you and me, Bradley tipped better than Eisenhower did. When I was able to go to school in my early years, my third grade teacher, Ms Harris, convinced be that one day I would be a writer. I heard her, but I knew that I had to leave Georgia, and unlike my friend Ray Charles, I did not go around with Georgia on My Mind. Instead, my best friend, Roscoe Hester use to sit with me spellbound, as I detailed the history of Timbuktu. I soon took a slow moving train out of Georgia because I did not want to end up like Richard (Dick) Wright's Black Boy. I came to New York, via Chicago and then I enlisted in the army and earned the rank of Master Sergeant. Later, I selected Harlem as the laboratory where I would search for the true history of my people. I could not stomach the lies of world history, so I took some strategic steps in order to build a life of scholarship and activism in New York. I began to pave strong roads toward what I envisioned as a mighty walk where I would initiate, inspire and help found organizations to elevate my people. I am thinking specifically of The Harlem's Writers Guild, Freedomways, Presence African, African Heritage Studies Association, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, National Council of Black Studies, Association for the Study of Classical African Civilization. I became an energetic participant in circles like Harlem Writer's Workshop, studied history and world literature at New York and Columbia Universities and at the League for Professional Writers. And, much like the Egyptians taught Plato and Socrates what they eventually knew, I was privileged to sit at the feet of great warriors like Arthur Schomburg, Willis Huggins, Charles Seiffert, William Leo Hansberry, John G. Jackson and Paul Robeson. Before I go any further, let me assure you that I always made attempts at structuring a holistic life. My three children are products of that reality. My oldest daughter, who kind of grew up with me, became a warm and wonderful young woman. Unfortunately, she preceded me in her passage. Part of my life's mission has been to deliver a message of renewal, redemption and rededication for young people all over the world and I hope the walk has afforded me that claim. So, now and in my traditionally fatherly way, I appeal to my two younger children, Sonni Kojo and Nzingha Marie to appreciate my commitment to them and the rest of the world. Sonni, in forming your identity, I called upon the spirit of Sonni Ali, the great Emperor of the Sudanic Empires to anoint you; and Nzingha, my second daughter, I reached back for the spirit of the warrior Queen Nzingha to lay her hands upon you. I have always felt blessed by the many nieces and nephews who have surrounded me: John H. Clarke, Charlie Mae Rowell, Walter L. Hobbs, Lillie Kate Hobbs, Wanda D. McCaulley, Angela M. Rowell, Maurice Hobbs, Vanessa Rowell, Calvin T. Rowell, Michael J. McCaulley, Madalynn McCaulley and a host of other extended family and friends. Lillie, I have always loved and needed the special touches of our relationship; without you this walk would not have been completed—I have not left you.

When the European emerged in the world in the 15th and 16th centuries, for the second time, they not only colonized most of the world, they colonized information about the world, and they also colonized images, including the image of God, thereby putting us into a trap, for we are the only people who worship a God whose image we did not choose! I had to respond to this behavior. I could not live with this nonsense and contradiction and I challenged these insidious concepts and theories. While I have not finished my work and I remain worried about who will replace Dr. Ben and me, I am not displeased of my progress of 83 years. As we all would agree, the struggle is continuous. I have utilized several avenues: I wrote songs and while most of you are familiar with the Boy Who Painted Christ Black, I wrote some two hundred short stories. I question the political judgment of those who would have the nerve to paint Christ white with his obvious African nose, lips and wooly hair. My publications in the form of edited books, major essays, and book introductions are indeed important documents and number more than thirty, Africa, Lost and Found with Richard More and Keith Baird, and African People at the Crossroads are among the major publication used in History and African American Studies disciplines on college and university campuses. I am also honored to have edited books on Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey. Through the United Nations, I published monographs on Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois; and, to clarify the historical record, I was compelled to publish a monograph on Christopher Columbus and the African Holocaust. One of my latest works, Who Betrayed the African Revolution?, was a very painful project, indeed. And, when I think of William Styron's error with Nat Turner and our response to it, I feel convinced that Nat was able to return to his rest in peace. Among the paths of my journey, I have had a chance to engage in dialogue at the major centers of higher education throughout North and South America, Africa and Europe. I am humbled by these opportunities and, I have been blessed as the recipient of a number of honorary degrees. My professorships at the Africana Studies and Research Center at Cornell University (where my portrait hangs at the artistic genius of Don Miller) was very important for the young men and women I taught there, and the work that I did with African and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College between 1965 and 1985 was highly significant. I have walked majestically with kings and queens and presidents and other heads of states. My special destiny with Africa, early on in this walk, afforded me the opportunity to mentor Kwame Nkrumah when he arrived in the United States as a student. The reciprocity of our relationship was manifested in my sojourn to post independence Ghana as a young journalist. Without question, my walk has been sweeter because I have shared the path with Kwame Nkrumah, Betty Shabazz and Malcolm, C. Zora Neal Hurston, Jimmy Baldwin, Martin Luther King Jr., Richard Wright, Julian Mayfield, John G. Jackson, Cheikh Anta Diop, John O. Killens, Hoyt Fuller, Chancellor Williams, Drucella Dundee Houston. Well, what do you know, I am transitioning with all of these giants now and the process is much easier because all of you are here with me. This walk has been anointed by God and the list of walkers is endless, and all of you have touched me deeply. I humbly acknowledge Dorothy Calder, Diane James, Doris Lee, Adalaide Sanford, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, Barbara Adams, Judy Miller, Gil Noble, James Turner, Howard Dodson, Mari Evans, Haki Madhubuti, Selma White, William and Camille Cosby, Irving Burgess, Pat Williams and others too numerous to mention. As all of you must know, I made an early commitment to transfer my library to Black institutions in an effort to demonstrate my unlimited trust and respect to the black community. So, it is to the Atlanta University Center and to the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture where I have donated the majority of my books and documents. I entrusted this task to members of the Institute for African Research, the Foundation which will perpetuate those objectives for which I dedicated my life. This has really been a long marathon and there have been caregivers at my dehydration stations that kept vigil and in the spirit of love and devotion, I thank you for your deeds. Ann Swanson and Barbara True, your work with me has been unconditional and I ask you now to accept my gratitude and know that my spirit will always be your protective shield. Chiri Fitzpatrick and Derrick Grubb, you are very familiar with the parameters of this run and with me; you are of long-distance caliber. Jim Dyer, Andy Thompson, Les Edmond, and Debbie Swire, I thank you for walking in step with me and bracing me with your strength. In you I observed the ingredients of African kings and queens. Iva Elaine Carruthers and Bettye Parker Smith, I know that I have raised you the right way and you must now move with winds of my spirit wings. You know my literary agenda and you are obligated to manage that knowledge. The ancestors have stretched out their arms and I see them beckoning now at a distance. And, like Langston Hughes has known rivers, I have known love and bliss. Sybil Williams Clarke, whom I have known for over fifty years and now my wife of ten months and my companion and friend eleven years, has made this journey with me and made my life complete. But, Sybil, your loving touch, notwithstanding, your arms were not long enough to box with the eminent moment. But, while I must make this physical departure, spiritually, I will not leave you and God will take care of you. When you feel a cool breeze blow across you face every now and then, just know that it comes from the deep reservoir of love that I hold for you. Oh, by the way, Christ is Black; I see him walking at a distance with Nkrumah: I think they are coming over to greet me.

My feet have felt the sands

Of many nations,

I have drunk the water

Of many springs.

I am old.

Older than the pyramids,

I am older than the race

That oppresses me,

I will live on...

I will out-live oppression.

I will out-live oppressors.

"DETERMINATION"

July 16, 1998

The first in the series, John Henrik Clarke: A Great and Mighty Walk, chronicling the life of Dr. John Henrik Clarke, a pre-eminent voice and authority on African and Afro-Caribbean studies, won critical acclaim at the Sundance Film Festival in 1997 and won the Grand Jury Prize for Best Documentary at the Urbanworld Film Festival in New York.

End

No comments:

Post a Comment