uhuru and Power to the People,

uhuru and Power to the People,Brothas and Sistas, I bring this information to you in the name of liberation for all Africans. Analyze and get it around, we must begin to utilize new startegies if we are to liberate our continent and restore balance. Every day our resources are raped from the continent and everyday we delay the excuse will grow, thatr it is not our land. The reality is we must reclaim Africa now, and it begins in America. let us learn from the strategies employed by others and move forward. let us use our national names as identities and add that our culture is Black, black is beautiful.

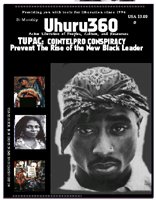

The following excerpt is from uhuru360 magazine on sale now @ your local afrocentric bookstore, if its not there ask them to get it there, contact us.

This article is submitted by field agent. johnny quest.Brooklyn

Although COINTELPRO formally ended in 1971, at least one ex-FBI agent stated that the FBI informally continued the same

program by framing it in different terms.11

Particular evidence of COINTELPRO’s informal continuance has come out in classaction suits in New York City.

In a landmark case challenging COINTELPRO activities in New York City, “[Police] Commissioner Murphy conceded that the Police Department was engaged in the vast bulk of activities described in [the class action] complaint, including surreptitious

surveillance and undercover infiltration of the political activities of individuals and groups.”12 The class action suit,brought by a coalition of activists, also exposed the activities of “physical and verbal coercion...provocation of violence, and recruitment to act as police informers,” against New Yorkers involved in lawful political and social activities.13 One Panther

historian noted that “at least five BOSS [Bureau of Special Services] agents were planted inside the Panther Party almost from its inception, beginning at once to worm their way into positions of power.”1

The settlement of this case led to a court order in 1985 stipulating specific “Guidelines” for future police activity.15 Police admitted there was a special unit called “The Black Desk” to monitor Black New Yorkers. BOSS illegal police surveillance on the Black Liberation Movement in the 1980s, which included Tupac Shakur’s lawyer, Michael Warren, was found to have

violated the Guidelines in a 1989 opinion.16 Statewide, the JTTF, an FBI-police amalgam, had hunted down Mutulu Shakur, among other “terrorists,” and harassed their supporters.17

The question remains whether the COINTELPRO activities carried out by BOSS under the auspices of The Black Desk, and JTTF, were continued under a different police unit name in the 1990s. Often described as the special elite police unit with an almost completely white racial make-up, New York City’s select Street Crime Unit would be the most likely candidate.18

New evidence detailed below suggests that COINTELPRO tactics against Blacks in particular may have been behind the first near-fatal shooting of Shakur in New York in 1994.

Fame and Politics By the end of the Reagan/Bush era, Shakur’s auspicious musical debut, including lyrics discussing his Black Panther family, coupled with leading movie roles, threatened to bring the Panthers back into vogue.

Thus it is no coincidence that Shakur attracted police attention in direct proportion to his fame and success. In line with Shakur’s quote, “I never had a record until I made a record,” shortly after his successful solo debut, Oakland police ticketed him for jaywalking, then arrested and beat him in custody.19 Shakur’s first record, 2Pacalypse Now, railed against the FBI, the CIA, and President Bush. In 1992, a year after that album’s release, Vice President Dan Quayle, and later Senator Bob Dole, singled him out as responsible for police deaths.

With the FBI watching Shakur since he was a teen, and his leadership in the New Afrikan Panthers, a group dedicated to replicating the Black Panthers,20 police involvement in his life deserves more scrutiny.

While Shakur’s lyrics often dramatized inner-city life, including what some might view as negative images, glorifying gang life and denigrating women, they also included many positive political messages: ideas about Malcolm X and various Black Panthers.21 As a youth, Shakur performed benefits for Black Panther prisoners. By nineteen, he sang with the Grammy nominated band Digital Underground. Besides his stint as a Panther Chairman and his Underground Railroad/Thug Life Movement, Shakur participated in a Stop the Violence program, helped with a home for at-risk youth, sponsored a “CelebrityYouth League,” joined Central American solidarity benefits, and regularly spoke at rallies for voter registration and progressiveactivist groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment